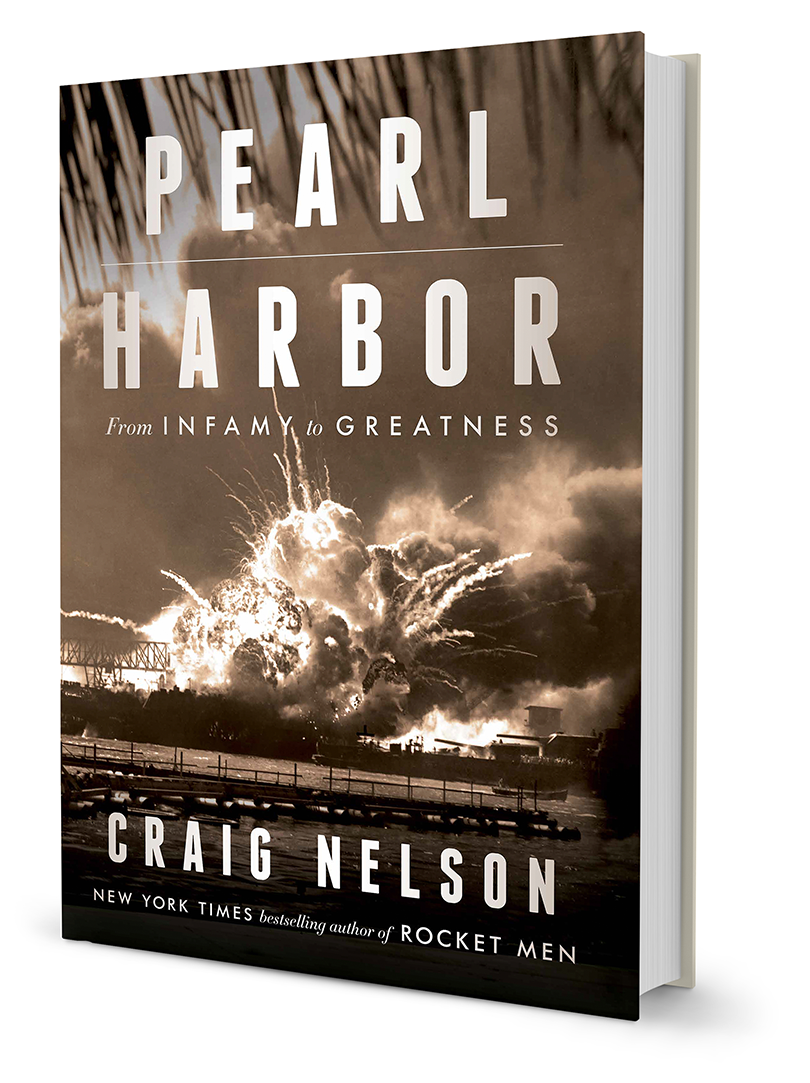

A Talk About Pearl Harbor

Why did you write this book?

On 9/11, I saw the second plane hit the World Trade Center from my roof deck about a mile away, I started being afraid of planes flying overhead. I’d see one and think, Why is it there? Where is it going? So I did research to try and cure this phobia, and discovered that thousands of Pearl Harbor survivors had the exact same fear. I’d written The First Heroes about the American reaction to Pearl Harbor — how the Doolittle Raid inspired Americans to believe that the Allies might win World War II. Then, I realized the 75th anniversary was coming, and that this may be the last moment to capture that history before it all fades away. The median age of Pearl Harbor survivors is around 93. I knew the time was now.

What are the things most Americans don’t know about Pearl Harbor?

After five years of research, I’ve decided that Pearl Harbor is the most important moment in modern American history. America’s role on the global stage, the size of our state department and foreign aid programs, the creation of the strongest fighting force the world has ever known, the size of our intelligence agencies, the birth of our nuclear arsenal, and the fact that there has been no World War III in seven decades — all began at Pearl Harbor. After reading this book you will see how the country we live in today was born not on July 4, 1776 but on December 7, 1941.

How did it happen?

Japan’s rush to war with the United States has usually been portrayed as a unstoppable force headed by war-mongering fascists. Instead, nearly the whole of Japan’s navy did not want to attack American soil and it took a number of years for the army to cow them into it. Along the way, nearly every Japanese leader, from Emperor Hirohito to General Tojo to Admiral Yamamoto, had mixed feelings about going ahead, swinging back and forth between war and peace. During this tumultuous period, it would have been fairly easy for Washington to talk Tokyo into a treaty, and Pearl Harbor might never have happened.

Instead, when I looked at General Marshall and Admiral Stark’s memos to Roosevelt and Secretary of War Stimson’s diaries from that time, I found how frequently the U.S. military insisted that Oahu was an impregnable fortress, and that Japan would never attack it. This inspired Roosevelt and Secretary of State Hull to be diplomatically belligerent with Tokyo. Stimson said that he knew the Asiatic mind, and that the Japanese would only respond to roughness. Instead the Japanese felt like they were being pushed into a corner. Finally on November 5, 1941, the US navy and army admitted that Japan’s forces in the Pacific were far greater than America’s, and begged Roosevelt to stall for time. But it was too late. By that time, Japanese leaders were living in an echo chamber, hypnotizing themselves out of any kind of logic. It was impossible then, as it is now, for the U.S. military to create a defense strategy against an enemy that has lost its mind.

Why was this the day of infamy?

When they saw the situation turning hopeless, Japan’s ambassadors in Washington went behind the backs of their government to urge that Roosevelt directly write Hirohito a letter of friendship to resolve their nations’ differences. The president did it, but an army officer stationed at Tokyo’s cable office made sure that his message arrived too late at the Imperial Palace. That same Major Morio Tomura then delayed Tokyo’s own cable to Washington ending diplomatic negotiations, so that Pearl Harbor was attacked before the announcement was formally presented.

What are your favorite moments in the book?

One great story comes from the lead Japanese dive bomber, Zenji Abe. Years after the war when he was a police officer, Abe learned that Tokyo had not declared war before attacking America, and he was mortified with shame. He spent the 1980s traveling across Japan to find the surviving airmen who’d participated in the attack and convinced them to sign a letter of apology. He then tracked down the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association and the home address of one of its officers. Abe flew to Atlanta with his letter, spent two hours in a taxi getting to the house, and knocked on the door. He explained who he was in halting English, and showed the man his letter. The American sailor told the Japanese pilot that he could take his letter and shove it up his ass, and slammed the door. Crushed, Abe went home, but he refused to give up. He began the Japan Friends of Pearl Harbor Society, and convinced a group of his fellow pilots to come to Hawaii for the fiftieth anniversary. There they met a marine from the West Virginia, a bugler by the name of Richard Fiske, who had not only survived Pearl Harbor, but also the battle of Iwo Jima, which killed sixty-eight hundred Americans and nineteen thousand Japanese. Fiske called Iwo Jima “thirty-six straight days of Pearl Harbor.” The marine had spent his postwar decades so filled with loathing for the Japanese that thinking about them made him physically sick.

When Fiske met the men who had been his lifelong enemies in person and suddenly saw them as human beings, as soldiers like himself, he “suddenly hugged me,” Takeshi Maeda said. “He was maybe as tall or a little taller than me. And I saw tears coming out of his eyes. And I told him, ‘I’m sorry for sinking your ship.’ But he said, ‘No, don’t say sorry, because it was a war between two nations. And we were soldiers, and it was our duty to fight. And there is no need for you or I to be sorry.’ ”

Later, Richard Fiske said: “We didn’t even shake hands, we just hugged each other. I’ll never forget that. Bringing the Japanese veterans and the American veterans together . . . I think it’s one of the greatest things that ever happened. Because it shows the world that here are two opposites, and now they’ve clasped their hands in friendship.”

After five years spent on this history, and so much of that time seeing the worst that people can do, I was so happy to see the best …

Some Pearl Harbor mysteries remain to this day. On November 22, 1941, a series of ads appeared in the New Yorker magazine for what was called “Chicago’s favorite game: THE DEADLY DOUBLE.” Under the headline “Achtung, Warning, Alerte!” it pictured a group of people sheltered from an air raid, playing dice numbered 12 and 7 — numbers on no known dice. Military intelligence investigated whether this was a secret warning, but every lead was a dead end. The ad’s copy had been presented in person at the magazine’s offices, and the fee paid with cash. Neither the game offered in the ad, nor the company that purported to make it, ever existed.

Another amazing story is that during the attack, a kitchen attendant, a busboy really, aboard the West Virginia, named Doris Miller, had just received a few hours of training in gunnery. Miller jumped onto an antiaircraft cannon and became one of the heroes of Pearl Harbor. But because he was black, he received a Navy Cross instead of a Medal of Honor. Doris Miller then died a few years later when his ship went down outside the Philippines, but the unfairness of his not getting that Medal of Honor made him an emblem for the civil rights movement, that eventually led to Harry Truman finally integrating the defense department in 1948.

One of my favorite discoveries was finding out that the first official news from Washington that Americans heard was from Eleanor Roosevelt, who had a weekly radio show on Sundays, listened to by 45 million. Every listener knew the Roosevelts had four sons all serving their country.

One last great one: When the man who led Japan into war, Hideki Tojo, was captured by the Americans, an American dentist made him new dentures. And he had ‘Remember Pearl Harbor’ inscribed into them in Morse code.

How did you research this story?

December 7, 1941 is the most written-about moment in American history, and when I first started out, the job seemed overwhelming. I decided that the solution was to redo the research from scratch through archives and libraries, and hired a team to help me. The key source materials are huge. The federal government’s archives in Washington is a stack of documents 48 feet long, 6 times the size of me, and arrives on its own trolley. Japan’s World War II documents have been published. They are 102 volumes. On top of all this were the memoirs and diaries of the key figures on both sides. The five years of research produced almost a million pages of notes which became the foundation of this book.

What was the most difficult part of PEARL HARBOR to convey?

That old saying “If only one man dies, that is a tragedy. If millions die, that’s statistics” is true; it was very hard to get across the human drama of such a massive event. I tried to solve that by bringing the lost and the found back to life through the massive oral history archives, including the Pearl Harbor Survivors’ Association; the National Archives and the Navy in Washington; the state of Hawaii in Honolulu; and a Japanese-American trove in California. If I couldn’t reach them in person, at least I could honor their lives by letting them speak for themselves.

What would you like your readers to take away from this book?

Few Americans realize how dramatically this one moment changed America in every way. After you read this book, you’ll see what a signal and earth-shaking event Pearl Harbor was in American history. Everything that happened in the wake of 9/11, to take one example, in defense, in security, in intelligence, in diplomacy, was just an amplification of the United States reaction to Pearl Harbor. And those key changes are still with us, 75 years later …