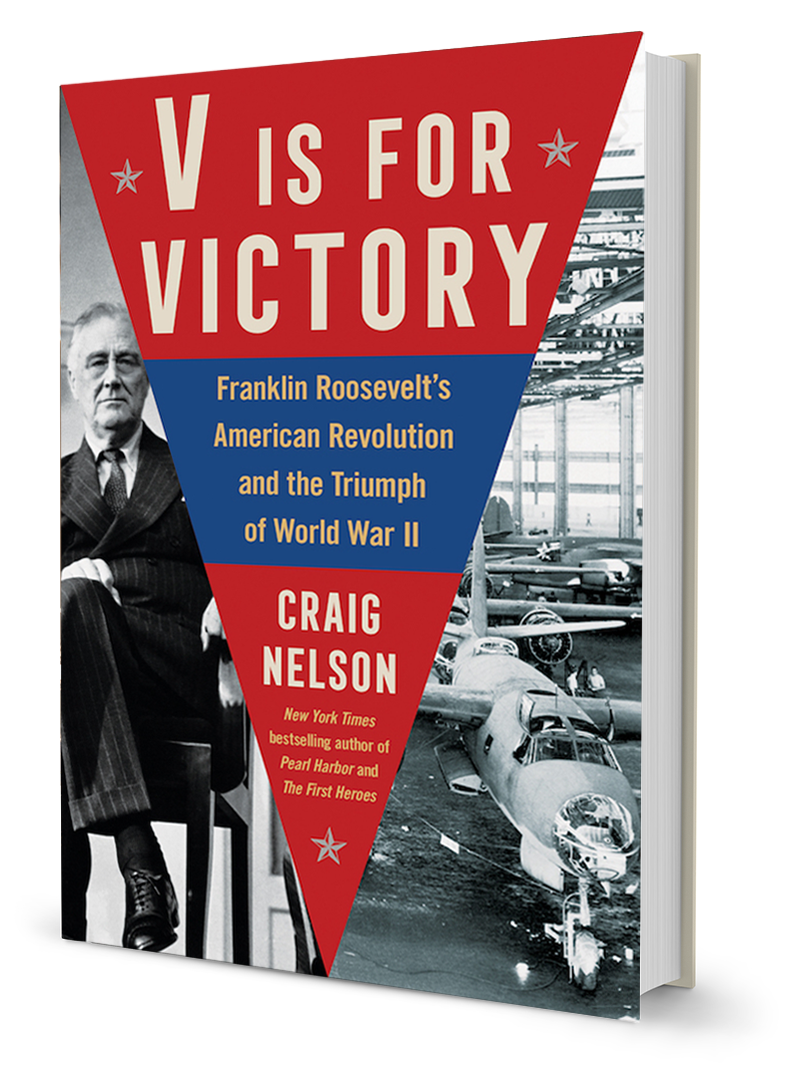

Sample Chapter of V is For Victory

On May 15, 2013, I buried my father in the Veterans Administration cemetery outside Aldine, Texas. He had himself buried my mother there fourteen years before. To save space, the VA’s policy was to intern couples on top of each other.

Mom and Dad had met while in high school in the neighboring Wisconsin towns of Tomah and Black River Falls, the former known for its cranberries and the comic strip Gasoline Alley, and the latter for its epidemics of suicide and diphtheria. My dad’s father was a successful electrician, and his family was relatively affluent; my mother was raised in the Great Depression in such rural hardship that one of her sisters was debilitated by rickets. Both were single when America entered the war, and soon after, my mother emigrated south and got a job working for air traffic control in Atlanta, living the busy life of a good-looking gal out on the town, with a coterie of new friends in tow.

My father, meanwhile, became an Army Air Forces sergeant, but the service’s tests had revealed him to be color-blind, which ended his lifelong dream of being a pilot. Instead, he was assigned to an AAF ground crew on the other side of the world in New Guinea . . . where one memory was cleaning up, after a Japanese air strike, the damage, and the bodies.

After their marriage, my parents fled Wisconsin’s winter terrors and rural hopelessness for the humid balms and zoning-free economy of Houston, Texas. In time, he became a business-management psychologist, and she, an administrator in the school district’s special education program. They had two sons, but except for an uncle who navigated B-52s across Asia, and a cousin and his son who rose to great heights in the U.S. Air Force, none of my family after V-J Day was involved with the military; we didn’t even hang out bunting on the Fourth of July. So it was strange to me that my parents wanted be united for all eternity, with my father receiving full military honors as a soldier, at a veterans’ cemetery, and one that was remarkably inconvenient for their descendants to visit.

When she was alive, my mother explained that they had made this decision because a Veterans Administration burial was free; for anyone as smacked down by the Depression as she was, little in life was as enchanting as the word free. But some years after both of their deaths, I came to know the truth. Being parents, and grandparents, as well as professionals who’d achieved the height of their careers, were not the most significant things that had ever happened to them. The most significant thing that had ever happened to them—and the very best years of their lives—was World War II.

-v-

Right now, the sun is low on the horizon, and the wind has turned sour. I write this on the seventy-fifth anniversary of V-J Day, which in America means the end of a war that required the United States to rise up from geographic solitude, economic depression, and a military ranked in size between Portugal’s and Bulgaria’s, to defeat global fascism in two immense conflagrations on opposite sides of the planet. Those well versed in this history hold contrary opinions on nearly every aspect of it. If you live in Asia, it is known as the Greater East Asian War, lasting fourteen years, and beginning when Japan invaded China in 1931. If you live in Europe, it began when Germany and the USSR invaded Poland in 1939; if you live in Russia, it began with the Nazi invasion of the USSR in 1941; and if you live in the United States, it began with Japan’s attack on Hawaii that same year. If you are a contemporary historian, however, you likely believe in a start date of 1914 since, in so many ways, World War II was a continuation of World War I, with a Weimar intermission.

On top of these geographic differences are different points of view created by the flood of World War II biographies, histories, and memoirs. If the central figure in your war history is Winston Churchill, it is likely because on January 23, 1948, Churchill announced to the House of Commons, “For my part, I consider that it will be found much better by all parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history,” and so he (and his ghosts) did. There have been, ever since, a mob of readers fully engrossed by Churchill’s point of view, despite whatever secret axes his prose may be grinding. Similarly, if George Marshall is your central figure, it’s due to Forrest Pogue’s massive biography; and if you have offered center stage to Henry Stimson, it’s due to Yale’s microfiche release of his no-holds- barred (and very opinionated) diary.

Unfortunately in all of this, one figure is absent: Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He gave his life to his country and died before writing his own memoirs, and it has taken all these many decades to reveal that, if any one human being is responsible for winning World War II, it is FDR.

World War II’s various conflicts in Asia, Africa, Europe, the Pacific, and the Atlantic appeared unrelated . . . until Roosevelt united the hodgepodge into a global struggle for the American people, which he called “the Second World War.” He then promoted a new concept, “national security,” which meant an extending of the country’s interests and needs out into the world beyond the defense of the continental United States. His Atlantic Charter established the U.S., the U.K., and various antifascist nations into what FDR referred to as not the Allies, but the United Nations, while his Four Freedoms created a goal for why those United Nations needed to triumph, defeat fascism, and bring peace to the world.

Long before Pearl Harbor, FDR became convinced that the secret weapon in defeating Hitler would be the full-throttle unleashing of American enterprise. The arsenal of democracy he engineered to do just that produced 2.5 million trucks, 500,000 jeeps, 286,000 aircraft, 86,000 tanks, 14,400 naval and merchant vessels, 41 billion rounds of ammunition, and 2.6 million machine guns — two-thirds of World War II’s Allied matériel. Without America’s assembly lines, Joseph Stalin said, “We would lose the war,” and those assembly lines were fighting a war in and of themselves. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, the number of American casualties fighting in World War II was 1,078,514 (405,399 dead; 673,115 wounded). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were over 8,931,900 American war industry worker casualties (75,400 dead and 8,856,500 wounded) between 1942 and 1945; eight times as many as on the battlefields.

Across history, the “arsenal of democracy” has come to mean this miracle of American manufacturing.

When Roosevelt used the term, however, he meant the miracle of the American people.

-v-

Historians have charted two American revolutions, one establishing the country in 1776, and another ending chattel slavery in 1861. There was, however, a third: an American revolution begun in 1933, one that extended across the whole of Franklin Roosevelt’s presidency.

The Roosevelt administration turned the United States of America upside down to create a wholly new country that would become both the leader of the West, as well as the global force that ensured that there would be no World War III. The arsenal of democracy may have been the secret weapon for winning World War II, but there could have been no arsenal without the managerial experience and infrastructure achievements of the New Deal. By transforming what Americans thought of themselves and what they could achieve, the Roosevelt Revolution ended the Great Depression; defeated the fascists of Germany, Italy, and Japan; birthed America’s middle-class affluence and consumer society; led to jet engines, computers, radar, the military-industrial complex, Big Science, and nuclear weapons; triggered a global economic boom; and turned the U.S. military into a worldwide titan—with the United States as the undisputed leader of world affairs.

New Deal architect and Labor Sec. Frances Perkins summed up:

In retrospect one is amazed at the enormous scope of the program Roosevelt led; amazed that such a prodigious amount of the war supplies should have been produced with such speed, accuracy, and high quality. That they should have been delivered with such promptness and precision in the exact places where they were needed. That a civilian Army and Navy of twelve million should have been raised, trained, outfitted; and millions of men shipped overseas ready for combat of the most difficult and unknown kind. . . .

The miracle is that Roosevelt kept his head above the welter of administrative problems and technical adjustments and kept his eye on the objectives of highest importance. The miracle is that he managed to keep the whole machine moving in the direction which made victory possible and laid the foundation for peace.

At that time, one of America’s most popular magazines, Collier’s, announced, “We have had our revolution, and we like it.”