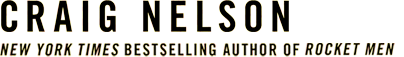

An Interview with Craig Nelson

Why did you want to tell this story?

I suddenly realized that that my mother and father’s life as parents, and grandparents, and professionals who’d achieved the height of their careers, was not the most significant thing that had ever happened to them. The most significant thing that had ever happened to them —and the very best years of their lives—was World War II. At the same time, I was randomly browsing through articles on military history, and came across some surprises. One said: “In wartime, logistics eats strategy for lunch,” which is pretty much the opposite of everything we’ve ever been told. Another mentioned Lincoln and Grant’s awful arithmetic: That, no matter how many battles the Confederates won, the Union, with its great advantage in supplies, would win the war. Another explained that the Germans thought they would win World War II because of Prussian military training, and the Japanese thought they would win because of their never-surrender Bushido philosophy, and the Americans thought they would win because they had the most trucks. Trucks won.

All of this went into what turned out to be my third book on World War II, and it’s filled with things I never knew. The secret weapon to winning that war was the arsenal of democracy, which had many of its roots in the New Deal, and became the most successful union of U.S. government and enterprise in history. It’s the story of how Franklin Roosevelt’s policies (alongside his Great Debate with Charles Lindbergh) turned the United States upside down to create a wholly new country that would become both the lynchpin to defeating Hitler and Tojo, the leader of the West, and the global force that ensured that there would be no World War III. V is for Victory is the story of how, by transforming what Americans thought of themselves and what they could achieve, FDR ended the Great Depression; defeated the fascists of Germany, Italy, and Japan; birthed America’s middle-class affluence and consumer society; and turned the U.S. military into a worldwide titan—with the United States as the undisputed leader of world affairs.

What was the Great Debate?

After his baby was kidnapped and murdered, the most famous American in the world — Charles Lindbergh — fled the ravenous press photographers of the United States to live in England. He was invited to tour the Luftwaffe in 1938, and afterwards announced: “Germany now has the means of destroying London, Paris, and Prague if she wishes to do so. England and France together have not enough modern warplanes for effective defense or counterattack.” None of this was true, but it made the rest of the world believe that the Nazis were unbeatable, while inspiring the British and French to appease Hitler by giving him a piece of Czechoslovakia and Roosevelt to launch a government-led expansion of American aircraft production. This policy, the first step of the arsenal of democracy, became a remarkable success, In 1939, France and England bought 6,000 engines from East Hartford’s Pratt and Whitney, 1,300 Hudsons from Burbank’s Lockheed, 815 Marylands from Baltimore’s Glenn Martin, and 100 Wildcats from Bethpage’s Grumman, while U.S. airframe production doubled, and aircraft engine output tripled.

By 1940, as the source of airpower for three nations, the United States outproduced Germany.

After the Nazis shocked the world with the brutal rioting, looting, murders, and police indifference to the attacks on German Jews that became known as Kristallnacht, when Lindbergh appeared in movie newsreels, American audiences hissed and booed. The aviator came to believe that, by talking Americans out of fighting the fascists, he might be a hero once more, and he returned home. Alarmed by Lindbergh’s influential support of the Nazis, Roosevelt invited him to a White House meeting. There, the president could employ the bounty of his charms to either convert Lindbergh into an ally, or at least try to get him to reduce his public cheerleading for Hitler. It didn’t work. On a radio broadcast carried by all three national networks, the aviator announced that America must “defend the white race against foreign invasion.”

When Roosevelt then won an historic third term as president, Lindbergh told his fellow Republicans that, “‘Democracy’ as we have known it is a thing of the past. . . . A political system based on universal franchise would not work in the United States. . . . One of the first steps must be to disenfranchise the Negro.” The conversation among the gathered Republicans then turned to “the Jewish problem and how it could be handled in this country.” Lindbergh said that, along with Americans of British descent and Wall Street bankers, “were it not for the Jews in America, we would not be on the verge of war today. . . . The more feeling there is against the Jews, the closer they band together; and the more they band together, the more the feeling rises against them. . . . We are not a moderate people, once we get started, and an anti-Jewish movement might be considerably worse here than in Germany.”

Just as millions of Americans would suffer the rigors of basic training to prepare for combat, the nation’s civilians would be prepared for the sacrifice of World War II by the duel of words between Roosevelt and Lindbergh, in its time known as the Great Debate. The fight between their camps of interventionists and isolationists had grown as heated as any American political conflagration, a near civil war that would escalate in the years before Pearl Harbor over the nation’s foreign policy, and then continue across American history with charged political brawls over immigration, border control, tariffs, treaty negotiations, and the draft. For all its violence, though, the Great Debate united the nation like no other moment in its political history by directly engaging the American public in discussing what was most important in their lives, and what kind of people they wanted to be. Over the course of 1939–41 (the road to Pearl Harbor), nothing was as important in swaying public opinion as Roosevelt’s public fights with Lindbergh.

What are some of the surprising things you uncovered about Winston Churchill?

The British failure to intervene in the 1940 Nazi attack on Denmark and Norway was essentially First Lord of the Admiralty Churchill’s fault. Yet, when the loss of Scandinavia ended Britain’s patience with Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s policies, he was replaced by . . . Winston Churchill, whose reputation at that moment was so awful that King George VI and the House of Commons were both fearful and horrified that he had risen to the height of British power. History is funny that way, since, looking back, what would we have done without him?

On January 9, 1941, FDR’s right hand, Harry Hopkins, arrived in London to assess the truth of whether or not the United States should continue to support Great Britain. Six weeks’ later, at his departure dinner, he announced: “I suppose you wish to know what I am going to say to President Roosevelt on my return. Well, I am going to quote to you one verse from the Book of Books . . . ‘Whither thou goest, I will go and where thou lodgest I will lodge, thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.’ Even to the end.”

Churchill openly sobbed. Hopkins then privately revealed FDR’s conclusion: “The president is determined that we shall win the war together,” he said. “Make no mistake about it. He sent me here to tell you that at all costs and by all means he will carry you through.”

My favorite Winston Churchill story, though, was told by Nicholas Soames, his grandson. In 1952, when Soames was all of four years of age, he ventured into Mr. Churchill’s bedroom one day to ask, “Is it true, Grandpapa, that you are the greatest man in the world?”

“Yes, I am,” Churchill replied. “Now bugger off.”

I read that the girl who grew up to be Queen Elizabeth II did volunteer work during World War II. What else did you learn about her?

At one point, the situation with Great Britain was so dire that the Commonwealth governments of Australia, Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand cabled Buckingham Palace to urge that the royal family, or at least the two little princesses, fourteen-year-old Elizabeth and ten-year-old Margaret Rose, be evacuated to one of their nations for safe haven. This would ensure that, whatever happened to the British Isles, the crown would continue.

In one of the great inspirational moments of World War II, the queen of England replied, “‘The children won’t go without me. I won’t leave the King. And the King will never leave.”

How did the success of the Allies on the battlefields start in the American industrial heartland?

Three years before Pearl Harbor, FDR became convinced that the secret weapon in defeating Hitler would be the full-throttle unleashing of American enterprise. He would boost the American economy while helping France and Great Britain defeat fascism, not with American lives, but with American tanks, trucks, and planes. His arsenal of democracy produced 2.5 million trucks, 500,000 jeeps, 286,000 aircraft, 86,000 tanks, 14,400 naval and merchant vessels, 41 billion rounds of ammunition, and 2.6 million machine guns—two-thirds of the war’s Allied supplies. Without America’s assembly lines, Joseph Stalin said, “We would lose the war,” and those assembly lines were fighting a war in and of themselves. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, the number of American casualties fighting in World War II was 1,078,514 (405,399 dead; 673,115 wounded). According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were over 8,931,900 American war industry worker casualties from 1942 to 1945 (75,400 dead and 8,856,500 wounded); eight times as many as on the battlefields.

Across history, the “arsenal of democracy” has come to mean this miracle of American manufacturing. When Roosevelt used the term, however, he meant the miracle of the American people.

How did the arsenal of democracy work?

Two weeks after the Nazis invaded France in 1940, Roosevelt asked Wall Street guru Bernard Baruch and financial wizard Jesse Jones to recommend the top industrial production men in the United States. Both had one name: General Motor’s Great Dane, Bill Knudsen.

Detroit was at this time the state of the art in production, the Silicon Valley of its day, having combined innovations from Colt guns, Singer sewing machines, Chicago meatpackers, and Sears Roebuck distribution into the assembly line where the product rolled across the factory floor or were carried overhead, with each worker assigned a specific task, needing a minimum of training. The speed and efficiency of this system meant that, every year, automobile prices decreased as they sold to more and more people.

At Ford Motor, Knudsen had launched twenty-eight factories nationwide, expanding the company’s sales from $90 million to over $680 million. Hired by GM to revive the money-losing entry-level-division Chevrolet, Knudsen applied what he’d learned at Ford and broke down production into stages to make it clear and efficient. In 1921, Chevrolet had sold 72,000 cars and lost $8.6 million; by 1922 under Knudsen, Chevrolet sold nearly 250,000 vehicles and made $11.2 million. His greatest executive breakthrough lay, however, not in engineering assembly lines, but in creating strong relationships with dealers and their repair operations, so that retail data—customer preferences and opinions —were sent back to GM and used to sell more Chevies.

When Roosevelt asked Knudsen to come to Washington to work on national defense, reporters were waiting for him; one asked, “Can you build those fifty thousand planes [FDR announced]?”

“I can’t,” he said, “but America can.”

Getting to work, Knudsen called one of his Detroit colleagues, K. T. Keller, the president of Chrysler.

“K.T., this is Knudsen. I need your help.”

“Sure, Bill,” said Keller. “What do you want?”

“I want you to make tanks.”

“I don’t see why not. What is a tank? Where can I see one?”

In time, the Chrysler Tank Arsenal would produce twenty-five thousand Grants and Shermans, more tanks from one Detroit factory than the Nazis produced over the whole of the war.

Knudsen’s great colleague in running the arsenal of democracy was Donald Nelson, the onetime chief of purchasing for the nation’s mightiest retailer—Sears, Roebuck—who enjoyed telling journalists that he oversaw a publication far bigger than any of their newspapers or magazines, the Sears catalog. If Ford and GM’s innovations in engineering and production made them the Apple of the early twentieth century, Sears, as a pioneer of direct-to- consumer sales, was the era’s Amazon. Balding, pipe smoking, patient, and overweight, Nelson was both a remarkable salesman and a logistics whiz who knew how to get the best deal on a certain amount and kind of fabric, how long it would take to mill and ship, and how to then coordinate its use for the manufacturers of curtains or rugs or children’s pajamas. An employee of Nelson’s for many years, Bruce Catton, said, “Quite possibly, he was the only highly placed man in Washington with neither a hidden agenda nor a ruthless will to power.”

Over the course of their time in Washington, both Knudsen and Nelson would be taught an elemental lesson, tha: everyone wants their military officers to be fighters, but no one wants those officers to be fighting them. It seemed incomprehensible to American generals and admirals that the men and women producing their guns, boats, planes, clothing, transportation, food, and lodging themselves required clothing, transportation, food, and lodging. Indeed, some officers regularly insisted that the United States would be far superior in every way if the military directly oversaw the national economy. That, however, would require the army and the navy to agree on something, which would be both a gross violation of military history and a violent undermining of American officers’ command prerogatives.

Over his first six months of doing business, Knudsen achieved a miracle, negotiating over $10 billion in contracts and putting 2 million Americans back to work while keeping inflation to a bare minimum. To those who didn’t understand the industrial process, however, it seemed as if little was getting done; that no progress was being made. Fortune magazine announced, “National defense is in pretty bad shape, and everyone in and out of Washington has seen the defense program drift and stumble.”

The bottleneck that undid Knudsen’s Washington career was the manufacture of machine tools—the machines that make other machines. Ranging in size from jewelry boxes to houses, machine tools are used to cut, shear, lathe, press, stamp, mill, scour, bore, drill, slice, plane, mold, trim, grind, and smooth metals, wood, cloth, and plastics; it took, for example, eighty-seven machine tools to manufacture a U.S. World War II propeller shaft. Machine tools were still an artisanal business, composed of a mere two hundred American firms, three of which dated back to the Revolutionary War. While under the Nazis between 1933 and 1938, Germany’s machine tool industry grew 800 percent to become the acknowledged global leader, the great majority of America’s machine tools had been made between 1850 and 1900 . . . forty to ninety years before Knudsen even arrived in Washington.

FDR eventually replaced Bill Knudsen with Donald Nelson, who achieved a breakthrough by overseeing four raw materials—aluminum, copper, carbon steel, and alloy steel. By asking how much of these resources were needed by the army, the navy, the Maritime Commission, Lend-Lease export, the Board of Economic Warfare, and the War Production Board’s Office of Civilian Supply and Aircraft Scheduling Unit, Nelson’s team could divvy up what each received, based on supply. Almost overnight, an immensely chaotic and uncontrolled situation was made organized and efficient, and the nation finally had a coordinated effort to produce nearly everything needed to fight the war.

What is the truth about Rosie the Riveter?

Rosie first appeared as a big band hit song in 1942. Kay Kyser’s “Rosie the Riveter” was “making history, working for victory, keeps a sharp lookout for sabotage, sitting up there on the fuselage.” The song was most likely based on Rosalind P. Walter, who appeared in an early newspaper story riveting F4U gull-winged Corsairs on Long Island. But there were at least six more Rosies, including Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post cover, modeled on the prophet Isaiah from Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, and J. Howard Miller’s biceps-flexing, polka-dot-bandanna-wearing Rosie, who announced on behalf of Westinghouse, “We Can Do It!”

The most famous American female war worker, however, never riveted. In 1944, Capt. Ronald Reagan’s U.S. Army Air Forces’ First Motion Picture Unit sent twenty-five-year- old photographer David Conover to shoot pictures of pretty war workers at the Radioplane drone plant in Van Nuys, California, for Yank magazine. Conover: “I came to a pretty girl putting on propellers and raised the camera to my eye. She had curly ash blond hair and her face was smudged with dirt. I snapped her picture and walked on. Then I stopped, stunned. She was beautiful. Half child, half woman, her eyes held something that touched and intrigued me.”

The pretty girl was a teenager, Norma Jeane Dougherty, who’d joined the assembly line after her merchant-marine husband Jim had shipped out to the Pacific. Yank never published Conover’s photographs of Mrs. Dougherty pretending to assemble a drone—her actual job was spraying parts with fire retardant—but Conover was so taken with her that he took two weeks off to create her modeling portfolio. These pictures got her a contract with Emmeline Snively’s Blue Book agency, and in twelve months Mrs. Dougherty would appear on the covers of thirty-three magazines. She then divorced her husband when he tried to stop her from working, got a contract with 20th Century Fox, and changed her name to Marilyn Monroe.

You have some incredible stories about women at war.

The greatest spy in the history of World War II, man or woman, was American agent Amy Elizabeth Peck, code name Cynthia. A product of Washington, Switzerland, and Newport, Peck once said, “I did my duty as I saw it. It involved me in situations from which respectable women draw back. But wars are not won by respectable methods.” Cynthia had been the key to getting detailed information about the Nazi Enigma cryptographic machine out of Polish mathematicians besotted with her charms. In Washington, she resumed an affair with an Italian naval attaché who arranged for her to have a copy of his service’s codebooks, which would be used in the British torpedo attack on Italian battleships anchored in the Ionian Sea, a mission known as Taranto and so successful that it inspired the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor. Cynthia next launched an all-consuming affair with Vichy press attaché Charles Brousse, who, as a token of his love, gave her the decryption key to the French naval codes, which were used to great success in Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa.

In a remarkably happy ending to all this derring-do, Ms. Peck eventually married Captain Brousse, and the two settled in the south of France.

What is the most surprising thing you learned about Franklin Roosevelt?

One was seeing that Ronald Reagan wasn’t the first president to bring acting to politics. Meeting Orson Welles, Franklin Roosevelt whispered, “Orson, you and I are the two best actors in America!” As president, he created a persona he wore like a cloak: a relentlessly sunny, supportive, undereducated, and wholly naive charmer who found the world beautiful, liked everyone in it, and agreed with everything anyone ever said. While the FDR of the fireside chats and the speeches to Congress was sweet and warmhearted, one biographer who grew to know FDR over decades of research concluded that going to meet Roosevelt in the White House was like visiting the den of a spider.

Reporter John Gunther remembered a press conference where “in twenty minutes Mr. Roosevelt’s features had expressed amazement, curiosity, mock alarm, genuine interest, worry, rhetorical playing for suspense, sympathy, decision, playfulness, dignity, and surpassing charm. Yet he said almost nothing. Questions were deflected, diverted, diluted. Answers—when they did come—were concise and clear. But I never met anyone who showed greater capacity for avoiding a direct answer while giving the questioner a feeling he had been answered.”

New Deal aide Rex Tugwell concluded that FDR had vigorously practiced acting skills as part of his profession as a politician, “a lifetime part that he was playing, [and] no one would ever see anything else.” Later, Tugwell summed up, “There was another Roosevelt behind the one we saw and talked with. I was baffled, unable to make out what he was like, that other man.”

FDR was so effective in his “regular guy next door” persona in fact that, after the war was won, correspondent Quentin Reynolds was one of the few to realize about the arsenal of democracy that, “This enormous program must have been thought out and planned by someone. Could it have been the President?”

My other insight was that some of the most memorable eyewitness accounts of FDR’s administration, endlessly repeated in histories of the era, are from sources we have since learned were played all the way to the bank by Franklin Roosevelt. When at the end of 1940, U.S. military chiefs met with Roosevelt about making a great change in how federal policy was effected, Roosevelt was as frustrated as anyone with the status quo, but unsure of the way forward, so he did what he always did when he wasn’t ready to make a call: He started telling one frivolous and meandering story after the next until the passions in the room cooled, and everyone became more anxious for the meeting to end than they were for it to end in their favor.

A befuddled Secretary of War Henry Stimson then wrote in his diary one of the great quotes of World War II: “Conferences with the President are difficult matters. His mind does not follow easily a consecutive chain of thought but he is full of stories and incidents and hops about in his discussion from suggestion to suggestion and it is very much like chasing a vagrant beam of sunshine around a vacant room.” Stimson would never grasp that this was FDR’s feint for getting out of questions he didn’t want to answer or topics he didn’t want to discuss.

When Wall Street titan Bernard Baruch was promised a job, and arrived at the White House to announce, “Mr. President, I’m here to report for duty,” Roosevelt, who’d already decided not to give him that job, delightfully replied, “Let me tell you about Ibn Saud, Bernie.” He then told a rambling, inconsequential anecdote about the Saudis and their kingdom before running off to a cabinet meeting and never mentioning a word about Baruch’s job.

And you came across some surprising material about Eleanor.

I always thought of Eleanor Roosevelt as a kindly old grandma, but in this book, she’s practically a ninja. During Franklin’s run for vice president on the Democratic ticket in 1920, Eleanor’s cousin, Theodore’s son Ted Jr., called her husband “a maverick [who] does not have the brand of our family.” Four years later, when Ted Jr. then ran for governor of New York, he was followed close behind on his campaign stops by Eleanor in a car festooned with a gigantic steaming papier-mâché teapot, alluding to his involvement in the Teapot Dome scandal. ER regularly commented of her cousin that he’s a “personally nice young man whose public service record shows him willing to do the bidding of his friends.” Ted Jr. lost in a landslide— contrary to nearly every other Republican campaign that year—and his political dreams were cauterized.

After Eleanor determined that man responsible for keeping her son, FDR Jr., from becoming the governor of New York was corrupt Tammany politician Carmine DeSapio, she launched a reform movement that ejected DeSapio from Albany and kept him from state politics for the rest of his life.

But the most surprising Eleanor story started when her husband was almost assassinated.

After spending eleven days cruising aboard Vincent Astor’s yacht, on February 15, 1933, Franklin made an impromptu speech from his car in Miami. At the end of his talk, Chicago’s mayor Anton Cermak stepped up for a chat. There was the sound of gunfire. Cermak collapsed. As the Secret Service drove at top speed to the hospital, Roosevelt cradled the mayor in his arms and said, “Tony, keep quiet—don’t move. It won’t hurt you if you keep quiet.”

After Franklin was then elected to the White House, Eleanor announced that she would be going about her business without any assigned local police or federal Secret Service to guard her, even though she had amassed a great cabal of political opponents, and her husband had just survived an assassination attempt. Across her decades of public service, Mrs. Roosevelt would face innumerable threats while not being intimidated by anyone, which inspired the American public. It wasn’t commonly known however that, after marksmanship lessons provided by her bodyguard, Earl Miller, Eleanor regularly carried a gun in her purse.